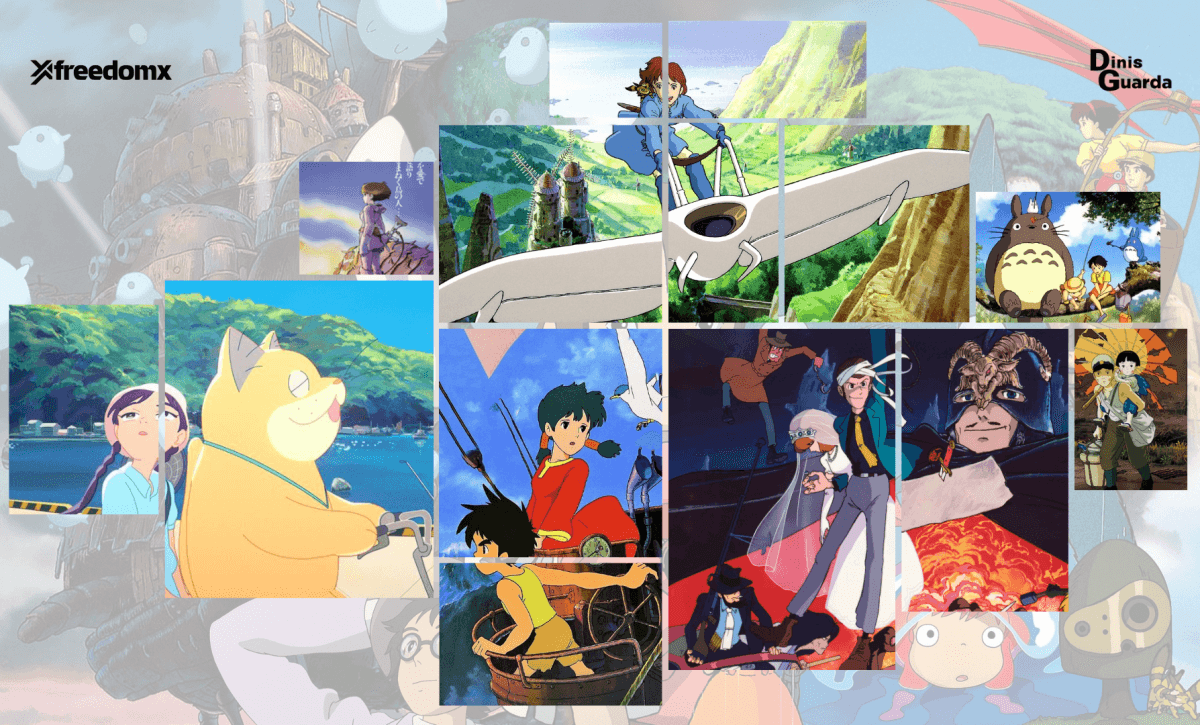

The era when anime earned its soul! The 1979-1988 golden age saw masters like Miyazaki and Takahata tackle war, nature, and childhood with breathtaking artistry. Let’s explore the revolution that gave us Nausicaä and Grave of the Fireflies, forever elevating animation from entertainment to high art.

The period between 1979 and 1988 marks a significant renaissance in the world of anime, a time when the medium transformed from a form of popular entertainment into a revered art form, capable of profound emotional and philosophical exploration.

This was an era when animation, long associated with light-hearted storytelling and juvenile entertainment, reached artistic heights previously reserved for live-action cinema, poetry, and classical painting.

Across darkened theatres in Japan and around the globe, audiences discovered that animation could communicate complex, deeply human ideas, ideas about war, technology, nature, and the human condition. It was a time of artistic awakening, fuelled by a new generation of creators who were poised to redefine what animation could achieve.

The cultural renaissance: Japan’s artistic confidence

By the late 1970s, Japan had emerged from the ashes of World War II as a global economic powerhouse, its post-war economic miracle powering the country into the ranks of the world’s most influential nations.

This success was mirrored by a cultural renaissance in which Japanese artists, writers, and filmmakers found an audience not only within Japan but across the world.

Japanese art was celebrated for its unique ability to blend modernity with traditional culture, providing fertile ground for new artistic expressions.

Alongside this cultural boom, environmental concerns were becoming ever more prevalent. With Japan’s rapid industrialisation came an acute awareness of its ecological consequences. The traditional reverence for nature embedded in Japan’s Shinto beliefs provided a framework for tackling contemporary environmental issues.

Simultaneously, the impact of Japan’s wartime history and its implications for national identity were being explored in new, sensitive ways. The emerging generation of creators, born after the war, was eager to understand their nation’s history while forging new paths in their relationship with the global community.

This generational shift allowed for more sophisticated reflections on the themes of war, peace, and human nature, creating a fertile soil for anime to flourish as a medium capable of addressing deeply philosophical and social concerns.

The emergence of auteur animation

In the world of live-action cinema, the concept of the “auteur” had long been established, particularly following the French New Wave in the 1960s. An auteur was seen as the director who shaped a film with their unique creative vision, often imbuing the film with a personal and thematic depth that set it apart.

However, in the world of animation, this idea had remained largely unexplored. Until the late 1970s, animation was primarily seen as a collaborative medium where the individual voice of a director was often subsumed within the commercial demands of the studio.

The late 1970s and 1980s, however, saw the rise of auteur animators who brought their distinct, personal voices to the medium. These directors infused their works with thematic consistency and artistic depth, allowing animation to be recognised not just as an entertainment medium but as a legitimate form of artistic expression.

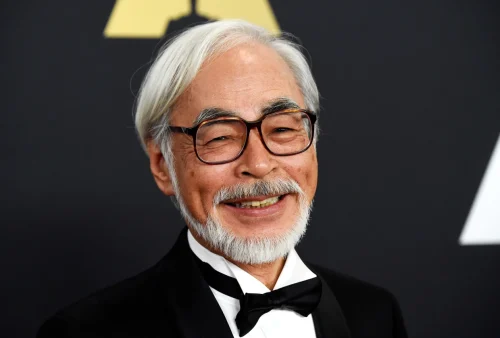

This period witnessed the birth of an anime auteur – Hayao Miyazaki.

Hayao Miyazaki: The poet of animation

Hayao Miyazaki, perhaps the most influential figure of this period, became synonymous with the artistic awakening of anime. Born in 1941, Miyazaki’s rise to prominence as an auteur came at a time when animation was beginning to mature, and his works would come to define the very essence of anime as an art form.

Early career and artistic development

Miyazaki’s career was built upon a deep technical understanding of animation, which he honed through his work at Toei Animation starting in 1963. Over nearly two decades, he mastered every aspect of animation production, from in-between animation to key animation to scene design. His technical expertise would later serve as the foundation for his uniquely ambitious creative visions.

His early work on television series such as Future Boy Conan (1978) displayed his growing artistic sensibilities, while his collaboration with Isao Takahata on The Castle of Cagliostro (1979) showcased his ability to craft feature-length narratives with both adventure and heart.

These projects allowed Miyazaki to experiment with the storytelling techniques and thematic depth that would later define his body of work.

“Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind” (1984): The Environmental Epic

Miyazaki’s breakthrough came with Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), a film based on his own manga series. The film was groundbreaking, not only for its environmental themes but also for its technical and artistic innovations.

Nausicaä was more than an adventure story, it was an epic exploration of humanity’s relationship with nature, set against a post-apocalyptic backdrop. The film’s narrative depth avoided simplistic moralizing and instead presented a nuanced view of environmental destruction, recovery, and human resilience.

The character of Nausicaä, a young princess with a deep reverence for nature, embodied the themes of the film. She was scientifically curious, environmentally aware, and committed to understanding the natural world rather than conquering it.

This character represented a fusion of traditional Japanese values, respect for nature and community, and contemporary concerns like environmental activism and scientific literacy.

Visually, the film was a triumph. Miyazaki’s intricate and evocative depictions of the toxic forests, simultaneously beautiful and terrifying, set a new benchmark for animation. The colour palette, dominated by earth tones and organic textures, created a unified visual identity that enhanced the environmental themes of the film.

International recognition and cultural impact

Nausicaä became an instant classic in Japan, garnering critical acclaim and establishing Miyazaki as a global auteur. The film was lauded for its profound environmental message and its visual beauty. Its international success demonstrated that anime could tackle serious themes while still appealing to a wide audience.

This was the moment that anime stepped into the international limelight as an art form capable of addressing contemporary global concerns.

The Formation of Studio Ghibli (1985)

Following the success of Nausicaä, Miyazaki and Takahata established Studio Ghibli in 1985, a studio dedicated to producing high-quality animated films. Ghibli’s founding marked a decisive shift in the anime industry, moving away from the television-focused production model towards a more ambitious, auteur-driven approach to filmmaking.

The studio’s approach emphasised quality over commercial expediency. Unlike the traditional studio model, where projects were often completed on tight schedules and budgets, Studio Ghibli provided its creators with the time and resources necessary to produce works of profound artistic value.

“Castle in the Sky” (1986): The Adventure Perfected

Studio Ghibli’s first official production, Castle in the Sky (1986), was a cinematic triumph. It combined adventure storytelling, environmental themes, and stunning visual spectacle in a way that set the stage for all of Ghibli’s future works. The film’s exploration of mechanical design, a recurring theme in Miyazaki’s work, demonstrated the studio’s technical excellence, while the film’s environmental subtext continued the exploration of humanity’s relationship with technology and nature.

Isao Takahata: The Realist Poet

Isao Takahata, Miyazaki’s long-time collaborator, provided a crucial counterpoint to Miyazaki’s often fantastical work. Takahata brought to animation a commitment to realism and social commentary, addressing contemporary issues with emotional depth and sensitivity.

“Grave of the Fireflies” (1988): The War Film Perfected

Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies (1988) is widely regarded as one of the most powerful anti-war films ever made. Based on Akiyuki Nosaka’s semi-autobiographical novel, it tells the story of two children struggling to survive during the final months of World War II. Takahata’s refusal to sentimentalise the story, instead focusing on the painful reality of war, helped the film to achieve a level of emotional honesty that few animated films could match.

Thematic and Visual Impact

The film’s realistic animation style, which contrasted sharply with the more stylised approaches typical of anime, grounded the film in a sense of authenticity. The documentary-like realism of the film, coupled with its intimate focus on the human cost of war, demonstrated anime’s potential to engage with sensitive historical subjects in ways that resonated universally.

Artistic Achievements and Milestones (1979-1988)

The decade saw several key releases that would shape the future of anime and define this golden period.

| Year | Title | Director | Studio | Artistic Achievement | Cultural Impact |

| 1979 | Galaxy Express 999 | Rintaro | Toei | Space opera artistry | International recognition |

| 1981 | Mobile Suit Gundam | Yoshiyuki Tomino | Sunrise | Compilation film innovation | Franchise expansion |

| 1983 | Golgo 13: The Professional | Osamu Dezaki | TMS | Adult animation breakthrough | Mature themes |

| 1984 | Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind | Hayao Miyazaki | Topcraft | Environmental epic | Auteur emergence |

| 1986 | Castle in the Sky | Hayao Miyazaki | Studio Ghibli | Adventure perfection | Studio establishment |

| 1987 | Royal Space Force: Wings of Honneamise | Hiroyuki Yamaga | Gainax | Technical innovation | New studio emergence |

| 1988 | Grave of the Fireflies | Isao Takahata | Studio Ghibli | Dramatic masterpiece | Anti-war statement |

| 1988 | My Neighbor Totoro | Hayao Miyazaki | Studio Ghibli | Childhood poetry | Cultural icon creation |

The expansion of thematic sophistication

The films of this period expanded the thematic scope of anime, exploring topics such as environmentalism, war, childhood, and personal growth.

Films like Nausicaä and Grave of the Fireflies brought complex, real-world concerns into the realm of animated storytelling, demonstrating that animation could achieve the same level of emotional depth and thematic sophistication as live-action films.