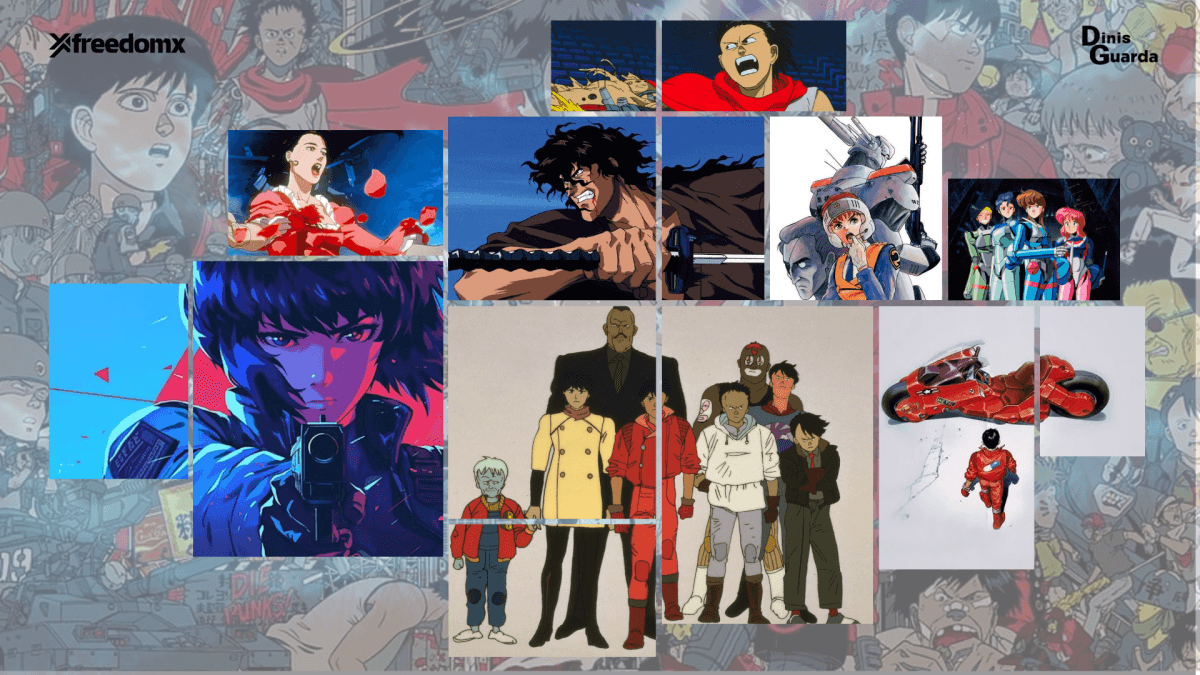

In 1988, a cinematic bomb detonated and anime was never the same. Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira didn’t just break box offices; it shattered the very perception of animation. How its cyberpunk vision of a decaying Neo-Tokyo sparked a global revolution, influencing everything from The Matrix to modern sci-fi, and forever changed the future of storytelling?

On 16 July 1988, Japan witnessed a cinematic earthquake. It wasn’t a natural disaster but rather a cultural one, one that reverberated through theatres across the globe. Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira exploded onto the screens with such force that it shattered preconceptions about what anime could achieve. It wasn’t just a film; it was a monumental shift in the global understanding of animation.

Akira was a cinematic revolution, offering up a visual spectacle that forever altered the landscape of animation, while also delving deep into philosophical and societal themes about technology, power, and the very nature of humanity. This film would mark the beginning of anime’s globalisation, pushing the boundaries of art and storytelling in ways previously unimaginable.

The period from 1988 to 1995 was a transformative time for anime, from being a primarily domestic Japanese medium to becoming a global cultural phenomenon. Akira was the vanguard, but it didn’t operate in isolation. It was part of a much larger movement that explored issues of urban decay, technological anxiety, and humanity’s search for meaning in an increasingly complex world.

The cultural context: Japan at the height of economic power

The Japan of the 1980s was a country at its peak, economically, technologically, and socially. The bubble economy had transformed the nation into an economic powerhouse, with Tokyo emerging as the ultimate symbol of modernity.

Skyscrapers made of glass and steel gleamed under the neon-lit skies, offering the promise of a utopia powered by technology. Yet beneath this glossy exterior, there were growing concerns, alienation in the city’s sprawling urban environments, environmental destruction, and a rising sense of spiritual and social emptiness.

Japan in the 1980s was in the throes of what could only be described as a paradox. It was one of the most technologically advanced nations in the world, yet it was also deeply conscious of the potential destructive power of that very technology.

The country was just a few decades removed from the devastation of World War II and the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These traumatic events cast a long shadow over the collective psyche of the nation. The generation coming of age in the 1980s was, for the first time, living in a Japan that had not known the horrors of war firsthand but had inherited the deep scars of its past.

The cyberpunk movement in literature and film, which had begun in the West, found fertile ground in Japan. Cyberpunk imagined futures where high-tech advancements coexisted with rampant social decay.

But Japan, with its unique cultural and historical context, was able to take these themes and delve much deeper, drawing upon its own anxieties about technology, power, and the human spirit.

The aesthetic of the technological sublime

One of the key elements that Akira and other works from this period excelled at was creating a visual representation of the “technological sublime.” This aesthetic, a term that describes the simultaneous sense of awe and terror that technology can inspire, was vividly brought to life in the dense, neon-lit streets of Tokyo.

The city itself, with its hyper-modern architecture and layered, constantly shifting media, provided a perfect backdrop for anime creators to explore the psychological and societal implications of technological advancement. The cityscapes depicted in Akira and other works captured a sense of both hope and dread, a theme that resonated deeply with audiences.

The sprawling urban environments, the giant billboards flashing with advertisements, the dark alleyways, and towering skyscrapers became characters in their own right. These cities were places of both wonder and danger, glittering facades hiding decay, as fragile as the human psyche under the weight of constant technological advancement.

Katsuhiro Otomo: The visionary behind Akira

If there’s one person who embodies the Akira revolution, it’s Katsuhiro Otomo. Born in 1954, Otomo was a manga artist and animator who would go on to reshape the landscape of anime. His work had always been characterised by intricate mechanical designs, dense cityscapes, and deep psychological insights into human nature.

As an artist, Otomo’s primary goal was to fuse visual spectacle with profound narrative complexity, something he achieved in spectacular fashion with Akira.

Otomo’s Akira manga, first serialised in 1982, was a sprawling, dystopian epic. The manga’s narrative was far too complex and expansive for a single film, which is why Otomo had to make significant adaptations when translating it to the screen. What emerged was an animated feature that pushed the boundaries of the medium in ways that had never been seen before.

His vision wasn’t just about creating an animated film, it was about transforming the very nature of animation. Otomo’s Akira would prove that animation wasn’t just for children. It was a medium that could explore complex, adult themes and engage in serious philosophical discussions about power, technology, and the future of humanity. It was Otomo’s unique blend of philosophical insight and technical expertise that made Akira not just an animation, but a global cultural event.

Akira (1988): The apocalyptic masterpiece

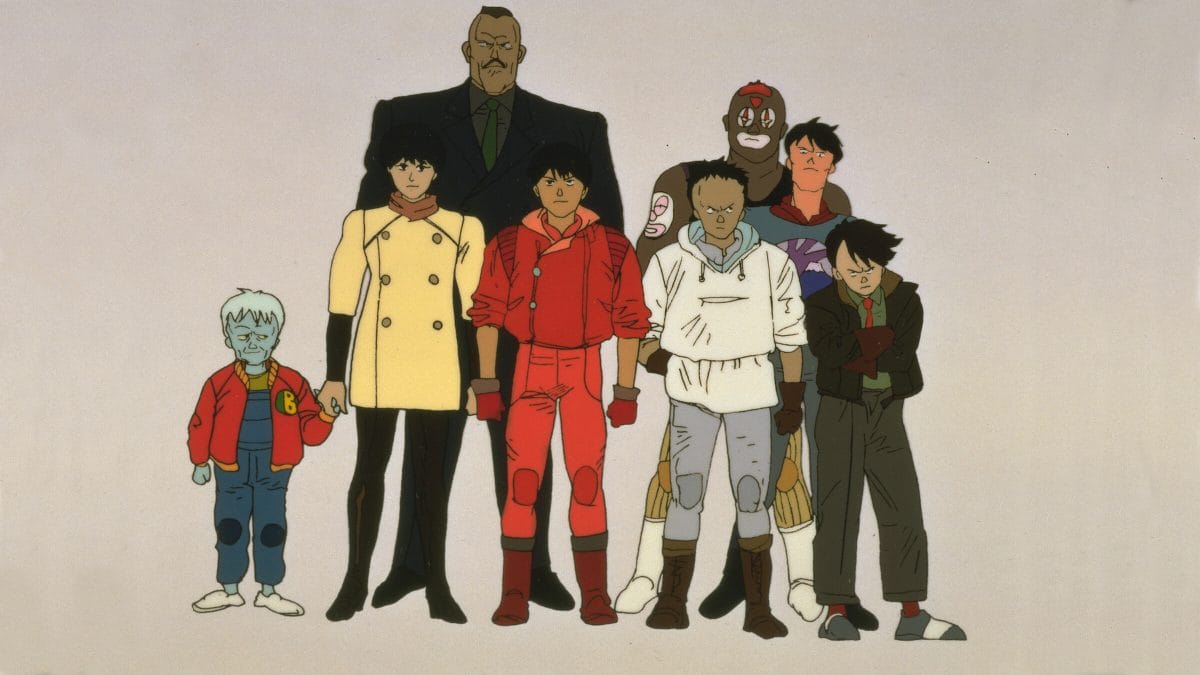

Akira wasn’t just a movie. It was an experience, one that left audiences reeling, questioning everything they knew about animation and its potential. The film, which followed the transformation of a young man, Tetsuo, into a god-like psychic being, was more than a tale of personal alienation and power. It was an exploration of the destructive potential of technology and the search for transcendence in a world on the brink of collapse.

At its core, Akira is about the tension between power and control. Tetsuo’s journey from a powerless youth to a being of unimaginable power serves as a metaphor for the dangers of unchecked ambition, technological advancement, and human potential.

The film didn’t just explore power as a concept, it asked fundamental questions about the nature of power itself: who controls it, and what happens when it escapes the boundaries of human comprehension?

The world of Akira, Neo-Tokyo, is a city that has been rebuilt from the ashes of nuclear destruction, yet it still carries the scars of its violent past. It is a perfect representation of post-war Japan, a nation trying to rebuild, yet constantly reminded of the darkness it had left behind.

Technical innovation and visual mastery

Aside from its thematic complexity, Akira set new standards for animation in terms of technical mastery. The sheer number of frames used, over 160,000 individual drawings, and the vibrant colour palette (using 327 colours) was a technical achievement that hadn’t been seen before in animation.

The level of detail in the background art and the intricacy of the mechanical designs brought a new depth to animation, one that allowed it to compete with live-action films in terms of visual sophistication.

The sound design, composed by Geinoh Yamashirogumi, integrated traditional Japanese instruments with electronic soundscapes, creating a unique audio environment that enhanced the otherworldly quality of the film. The combination of these elements made Akira not just a visual and auditory experience, but a complete immersive journey into a dystopian future.

The cyberpunk constellation: Expanding the revolution

While Akira is undoubtedly the central work in this period, it wasn’t alone in its exploration of technological anxiety and human transcendence. A host of other works, including Ghost in the Shell (1995), Ninja Scroll (1993), Patlabor (1989-1993), and Bubblegum Crisis (1992) were essential to shaping anime as the preeminent medium for cyberpunk storytelling.

Each of these works added new layers to the conversation about humanity’s relationship with technology, power, and identity. For instance, Ghost in the Shell (directed by Mamoru Oshii) explored the relationship between human consciousness and artificial intelligence, asking the question: at what point do we lose our humanity in the pursuit of technological enhancement? These works, while stylistically and thematically diverse, all share a focus on the psychological and societal implications of rapid technological growth.

The cultural influence on the West

One of the most profound aspects of Akira‘s success was its far-reaching influence on Western popular culture. The film didn’t just create a seismic shift in Japan; it left its imprint on Hollywood and the global entertainment industry.

Directors like the Wachowskis (best known for The Matrix) openly cited Akira as one of their major influences. The film’s cyberpunk aesthetic, characterised by a grim, neon-lit cityscape filled with towering skyscrapers and high-tech gadgets, would become the visual shorthand for futuristic dystopias in Western films. The themes of technological transcendence, the merging of human and machine, and the exploration of identity were all explored in The Matrix, showcasing how closely tied the two works are.

But Akira’s influence goes beyond just aesthetics, it also played a role in legitimising anime as an art form for adults. Prior to Akira, many in the West saw animation as a medium for children, reserved for Disney princesses and Saturday morning cartoons. Akira shattered this perception by not only addressing mature themes but also delivering them in a visually stunning way that appealed to both the intellectual and the sensory. This paved the way for films like Ghost in the Shell and Ninja Scroll to find international success, with Western audiences now eager to explore more adult-oriented animation.

Visual aesthetics and design: A neon-lit, decaying world

Akira and its contemporaries became known for their distinct visual aesthetics, specifically the juxtaposition of high-tech futuristic technology with the grime and decay of urban life. Neo-Tokyo, the city in Akira, is not just a backdrop but a living, breathing entity that mirrors the psychological states of its inhabitants.

The urban decay in Akira and similar works of the period is a reflection of the social and environmental anxieties of the time. Neo-Tokyo is a city rebuilt from the ashes of nuclear destruction, yet it still carries the scars of its violent past.

This is not a utopia of advanced technology, but rather a dystopia where technology is inextricably linked to societal breakdown. The characters live in a city of contradictions, one that is both technologically advanced and socially broken, a vision that perfectly reflects the cyberpunk genre’s thematic concerns.

The use of neon lighting and towering skyscrapers becomes symbolic of humanity’s struggle to maintain its humanity in a world that is increasingly dominated by technology. In this sense, the urban landscapes in Akira and other anime films of this era function not just as settings but as reflections of the characters’ psychological and emotional states.

Technological Anxiety and Spiritual Transcendence

What sets the cyberpunk anime of this era apart is its ability to address the dual nature of technology, its potential for both destruction and transcendence. While films like Akira and Ghost in the Shell explored the dangers of technology, they also suggested that there was hope for humanity’s transcendence through technological advancement.

In Akira, the psychic powers that threaten to destroy the world also serve as a means for the characters to reach new levels of consciousness. Tetsuo’s transformation into a god-like being can be seen as a metaphor for the potential for human beings to evolve beyond their physical limitations.

However, this potential is darkly mirrored by the destruction and alienation that accompany such power, suggesting that humanity must tread carefully as it approaches the boundaries of what technology can offer.

Similarly, Ghost in the Shell explores the idea of the human mind transcending its biological limitations through cybernetic enhancement. Major Kusanagi’s search for her own identity, as she questions what makes her truly human, presents a vision of technology as both a tool for evolution and a source of existential crisis.

These films raise important questions: What does it mean to be human when our consciousness can be uploaded, altered, or replaced? And if technology can enhance our minds, what spiritual costs do we pay in the process?

International recognition and cultural export

As anime began to achieve international recognition during this period, the business side of the industry also transformed. The success of Akira demonstrated anime’s commercial viability outside of Japan, paving the way for new distribution networks and co-production models that allowed larger budgets for ambitious projects.

The increasing success of anime on home video was a key factor in its global spread. The rise of VHS and later DVD allowed audiences in the West to watch anime in their own homes, helping build a dedicated fan base.

Akira, along with other works, also contributed to the expansion of anime merchandising, creating opportunities for global product tie-ins that helped fund production budgets and spread the aesthetic of cyberpunk anime into mainstream consumer markets.

Legacy and influence on future development

The period from 1988 to 1995 laid the groundwork for anime’s long-lasting cultural influence. The visual innovations and philosophical themes explored during this time continue to impact modern anime, while also influencing other art forms like graphic novels, video games, and film. The standards set by Akira for animation production, especially in the realms of hybrid techniques and sound design, are still being felt today.

The cyberpunk aesthetic that emerged in the 1990s remains a cornerstone of many futuristic films, television shows, and video games. Akira’s visual style, which blends the organic with the mechanical, continues to be a powerful influence, and the themes of existential dread and human evolution in the face of technology remain as relevant as ever.