The birth of modern anime wasn’t in a glittery studio. How did the post-war destruction in Japan spark the anime revolution? Explore the journey when iconic heroes like Astro Boy, Studio Ghibli and Tezuka Osamu turned anime into a global sensation.

When we think of anime today, we often picture vibrant, fast-paced shows with complex storylines and large fan bases. However, if we look back to 1945, Japan’s animation industry was far from being a global leader. It was fragile, emerging from the devastation of war, occupation, and a complete loss of its national identity. Japan had been scarred by bombs and defeat, desperately trying to rise again, much like the mythical phoenix.

The period from 1945 to 1963 was a time of reconstruction and change. During these years, anime evolved from propaganda tools and short films into emotionally engaging, commercially successful, and culturally significant works.

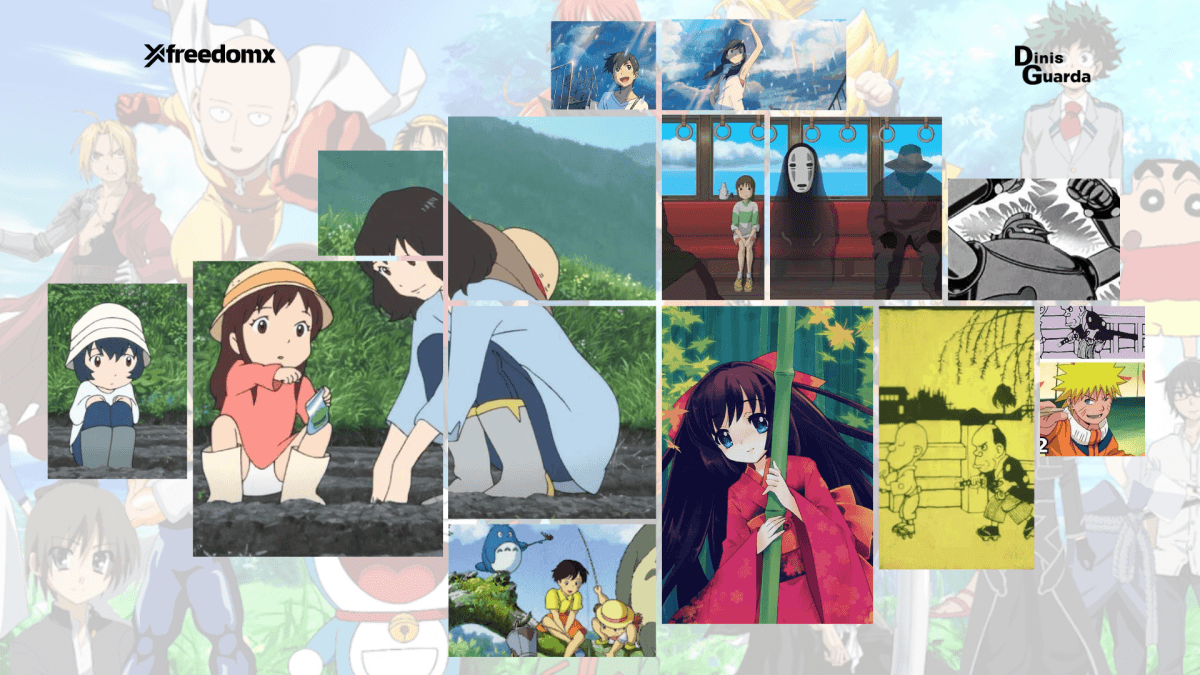

This era is often overlooked in favour of later decades that featured Astro Boy, Studio Ghibli, and a surge in global fandom. However, without the experimental ideas, resilience, and cultural adjustments of this early post-war period, the anime industry as we know it would not exist.

Japan in Ruins: The Ground Zero of Anime

Before anime became the popular art form it is today, it was very different in nature. The first steps of Japanese animation date back to the 1910s, but it was during the war that animation became firmly entrenched in Japan’s propaganda machine. Films like Momotarō: Umi no Shinpei (Momotaro: Sacred Sailors), released in 1945, were used to promote Japan’s imperial ambitions. However, when the war ended and Japan was occupied by Allied forces, the country found itself in a new cultural reality.

To understand the rebirth of anime, we need to look at the situation in 1945. Japan was in ruins after the war. Cities like Tokyo and Hiroshima lay in ashes. Industries were destroyed, and the economy fell apart. Animation studios, which had created wartime propaganda, were now under the control of a new authority: the American occupation led by SCAP (Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers).

Here’s the interesting part. SCAP discouraged open militarism and nationalism but promoted light entertainment to lift morale. On the surface, this seemed like harmless fun. However, anime and manga turned into a subtle space where Japanese creators could explore their identity. They were cautious enough to stay within censorship limits, yet bold enough to share their hopes, memories, and fears.

The emperor had acknowledged defeat. Families faced starvation. Yet, in scattered studios, animators began to pick up their pencils again. They sketched rabbits, children, and fantastical creatures. Animation became a quiet form of therapy, a way to rebuild culture.

The Leftovers: Early Post-War Animation (1945–1952)

Right after the war, Japanese animation was more about survival than revolution. Studios like Toei didn’t have much money yet. Independent artists were dealing with inconsistent support. The tough conditions forced creators to be resourceful. The paper was hard to find. Film stock was limited. Sometimes, animators recycled footage or made low-budget reels to show before films.

Still, amazing stories emerged. Artists drew from folklore, children’s tales, and glimpses of Western cartoons brought in by the U.S. Occupation forces. A mix of imitation and reinvention began. Walt Disney had a big impact; his work was displayed as a cultural influence, but Japanese animators turned that inspiration into more nuanced, local art.

This period planted the first seeds of what anime would eventually become: not just imitation but adaptation. Japanese animation took Western techniques and turned them into local cultural symbols, like traditional festival characters, childhood innocence, spirits, and resilience.

Toei Dōga and the Disney Dream

Here’s where things start to take off: 1956. Toei Dōga, now known as Toei Animation, was founded with the goal of becoming the “Disney of the East.” This ambition turned animation from a struggling artist’s pastime into a genuine industry.

Toei focused on producing feature-length animated films. Their big break came in 1958 with Hakujaden (The Tale of the White Serpent), which was Japan’s first colour anime feature film. You can think of it as their version of Snow White.

Hakujaden was innovative in style and held symbolic value. It was a retelling of an old Chinese folktale created in post-war Japan. Audiences were captivated. It demonstrated that Japan wasn’t simply imitating Disney; it was reinterpreting stories with a unique East Asian cultural perspective. A phoenix feather, if you will.

The success of Hakujaden also marked a significant shift: the notion that Japan could share its animation with the world. Suddenly, Japanese anime was not just for local kids’ shows. It had the potential to reach a global audience.

Tezuka Osamu: The Father and the Rebel

And you cannot talk about anime’s revolution without bowing to Tezuka Osamu. If Toei was building a Disney-style studio machine, Tezuka was exploding conventions with revolutionary ideas.

Tezuka, often dubbed the “God of Manga”, was already reshaping print comics. He pioneered cinematic panel layouts, dynamic characterisation, and emotionally complex storytelling. But he wasn’t satisfied with manga alone; he dreamt of animation that rivalled Disney’s storytelling magic yet carried uniquely Japanese heartbeats.

In 1961, he founded Mushi Productions. While Toei was making glossy feature films, Tezuka was scheming differently. He saw the future in television. Crazy as it sounds now, back then, the idea of regular anime broadcasts on domestic TV was risky. Studios believed big-screen features were financially safer.

But Tezuka had what economists call “disruptor energy”. He deliberately slashed production budgets, experimented with limited animation techniques, and focused on crafting emotionally gripping narratives instead of pure spectacle. Characters with oversized eyes? Yep, his stylistic choice, both borrowing from Disney influences and amplifying them into a new visual code, one that later defined anime aesthetics globally.

1963: Enter Astro Boy, the Revolution Ignites

The decisive moment arrived in 1963, when Tetsuwan Atom (Astro Boy) aired on Japanese television. And overnight, everything changed.

Here was a boy robot with a beating human heart, confronting questions about identity, morality, and coexistence. For children, it was entertaining sci-fi. For adults, it quietly explored post-war anxieties: rebuilding Japan through technology, the blurred line between humanity and machines, and the ethics of progress.

As soon as Astro Boy hit the airwaves, it wasn’t just popular. It was explosive. Merchandising kicked in, ranging from toys to sweets. Export deals followed, introducing anime to audiences beyond Japan. Suddenly, creators and studios realised something vital: animation could thrive outside cinema. It could become serialised, global, and commercial.

That was the revolution.

From the ashes of occupation, scarcity, and censorship, anime spread its wings.

The Broader Cultural Context

We can’t pull anime out of thin air without aligning it with Japan’s post-war identity struggle. Between 1945 and 1963, Japanese society was wrestling with the trauma of defeat, the cultural imposition of American values, and the rapid rebuilding into an economic powerhouse.

Two themes defined anime’s sensibilities in this era:

- Innocence and Resilience: Child heroes, whimsical spirits, anthropomorphic animals, not just for kids, but as metaphors for a nation trying to return to innocence after destruction.

- Technology and Humanity: From Tezuka’s robot boy facing ethical dilemmas to Toei’s explorations of folklore in modern formats, the balance between tradition and modernity was everywhere.

It was almost as if anime became a subliminal therapy session for Japan. Can we move forward without forgetting heritage? Can technology, once used for war, now be a tool for peace? These weren’t just national questions; they were baked into moving, breathing characters on screen.